Before I grew hair in my pink parts, my parents owned a video shop and I devoured all those horribly dubbed Chinese Kung Fu movies until I got indigestion. After watching those movies, I would “play fight” with my younger siblings in our own copyrighted animal fighting styles — the Bear, the Meerkat, the Lemur — while trying our darndest to make sure our lips and voices were nonsynchronous.

When we had the opportunity to vacation in (pre-Disneyland, pre-Mainland China handover, pre-Toys R Us in Ocean Terminal) Hong Kong, my siblings and I secretly wished that we would accidentally get lost in the teeming streets of Kowloon and turn down a wrong corner populated by those gangster stereotypes from our favorite Kung Fu movies. But before these hoodlums could accost any of us, my siblings and I would rip off our tops to reveal half-naked torsos rippling with muscles that were outlined by permanent marker (except for my younger sister), then we would spring into action with a fury of punches and kicks that would make asado out of would-be muggers. And God help any of the scoundrels who would try to pick themselves up from the ground: we would just scowl them back to unconsciousness.

And just who was responsible for inspiring these potentially life-threatening, pre-adolescent power trip fantasies?

None other than a real-life superhero — our Kato, our Big Boss, our Cheng Chao An: Bruce Lee. Sadly, my siblings and I are no longer able to recreate our childhood play-fight games (mostly due to gout), but I squealed with castrati-like glee when I found out that we could relive our Kung Fu-inspired childhood in the newly offered Hong Kong Wing Chun Experience/Bruce Lee tour.

Close Ad X

Yes, seriously. There is a Bruce Lee Tour.

The first stop was an opportunity to channel our inner Bruce Lee at the Yip Man Martial Arts Athletic Association Chinese Kung Fu International School for a crash course on the basic forms of Wing Chun. Yip Man (or Ip Man) was the instructor who brought over the practice of Wing Chun to Hong Kong from Guangdong, China in the early ‘50s.

Wing Chun is a popular form of Chinese martial arts (Wushu) that originated during China’s Qing Dynasty. Since there was no Facebook or text messaging back then, the “in” thing among the monks in the Shaolin temple was to learn and practice different forms of Wushu. During that period, a Shaolin nun named Wu Mei modified her fighting technique so it would be better suited for the smaller physiques and weaker physical strength of women versus men. This new fighting technique, which the nun said was inspired by watching snakes and cranes do battle, was in turn taught to a young girl named Yim Wing Chun so she could employ it in defeating a tyrannical warlord (which sounds suspiciously like the plot for a new Disney Princess movie).

Fewer than six people lay claim to have been personally taught by Yip Man. Among them are Bruce Lee and Sifu (which means “accomplished teacher”) Sam Lau, who was a first general disciple and assistant instructor of Yip Man in orthodox Wing Chun (since I have been exposed to Sifu Sam, I can now officially say that I am within six degrees of separation from Bruce Lee. Feel free to prostrate yourselves before me to feel Bruce Lee’s power through osmosis). When Bruce Lee (who incidentally was a San Francisco-born Chinese) migrated back stateside in 1959, he not only taught Wing Chun but he also adapted some of its techniques in his movies.

Sifu Sam explained that Wing Chun is one of the simplest, most effective forms of Wushu because of its economy of movement. He went on to demonstrate several signature moves: “straight centerline punches” delivered in rapid succession to the same body part of your opponent across a short distance to deliver a cumulative impact (Hmmm, could FPJ have been trained in the ways of Wing Chun?); outstretched fingers used to strike at the eyes, throat, chin and the most vulnerable pink parts of an attacker; low kicks to the knees and shin since these kicks are hard to defend against and help you maintain balance (versus mid- to high-level kicks). And, if the situation calls for it, Wing Chun will let you kick someone in the groin. (Was my yaya a Wing Chun master? Dirty Old Men representative: Yes, your yaya is a Wing Chun master.)

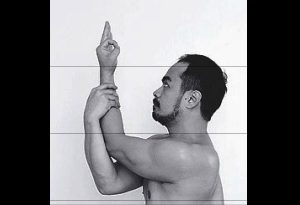

When I finally had the chance to Wing Chun it, Sifu Sam walked me through a series of movements, reminiscent of kata in Karate. I was made to thrust my arms back and forth while alternating between forming a fist and stretching out my fingers several times (perhaps my next kata would be waxing Sifu’s car?). Once I had a basic grasp of the hand forms, Sifu called in his son Max, who was also his assistant instructor, to “attack” me. After I stopped squealing like a castrati, Sifu reminded me to use the hand movements I had just learned to defend against my “attacker.” Sifu taught me how to throw Wing Chun’s fabled “one-inch punch” on a boxing dummy. Apparently, since you don’t pull back your arm to throw this punch, the power of the punch comes from the wrist (which means that many NGSBs reading this column are probably Sifus with the one-inch punch). The one-inch punch grows more effective when thrown in succession at the opponent’s centerline. If you throw enough punches, you start to grow sideburns.

The final technique that Sifu demonstrated was how to beat a defenseless wooden pole. No, no, NGSBs, the pole that I am referring to is the wooden training dummy called Mook Yan Jong, with slats that represent arms and legs which you often see getting beaten up in the training montages of Chinese martial arts films. This was actually one of my favorite parts of the course. Because nothing makes you feel more like a real man than beating up on a wooden dummy.

Since beating on wood can build up your appetite, we went for dim sum at the Mu Dan Ting Restaurant where Sifu taught us how to maim people using a pair of chopsticks while sharing with us his favorite dim sum dishes. After making sure that Sifu used utensils during the meal, we dropped by the Avenue of Stars along the panoramic Victoria Harbour to take pictures with Bruce Lee’s bronze likeness. For the sake of this column, I wanted to emulate the statue’s pose as closely as possible, but the Hong Kong police did not allow me to take off my shirt in public for national security reasons. Our last stop was a pilgrimage to the Hong Kong Heritage Museum for “Bruce Lee: Kung Fu, Art Life,” an exhibit that opened last year to mark the 40th anniversary of Bruce’s passing in 1973 (at age 32). It features over 600 pieces of memorabilia including class photos, personal journals, gym equipment, nunchuka, movie posters, lunchboxes, comic books, trophies, the mask from the Green Hornet series and his famous yellow tracksuit from the movie Game of Death. There’s lots of trivia that makes this icon just a little bit more human. For example:

He had a nickname. When the Golden Harvest film producers in Hong Kong were alerted to his performance in Green Hornet, they persuaded him to come back to Hong Kong to shoot The Big Boss (1971). The moviegoers were particularly taken with Bruce’s nigh-superhuman ability to deliver kicks in rapid succession that earned him the nickname “Bruce Three Legs.” (DOM representative: Did Bruce have a copyright on that nickname?)

The not-so-secret origin of Bruce Lee. Although Bruce grew up in an affluent community, his neighborhood was teeming with gangs that resulted from the spillover of refugees fleeing communist China. To keep from getting his derriere whipped by the neighborhood toughies, Bruce’s parents decided that he train with Wing Chun grandmaster Yip Man at the age of 13.

He was a Lasalista and a Xavieran! Just like TY Tang, one of my favorite basketball players, Bruce was a product of both the La Salle Primary School and St. Francis Xavier’s College (at first, I thought St. Francis was a Jesuit-run institution because of its Jesuit patron saint. But the College is run by the Marist Brothers). I had the opportunity to view some of his journals and noted the exquisite and unmistakable Palmer handwriting — the same handwriting taught to all La Salle students.

He was a child actor. Born to a famous Cantonese opera singer who was well connected to the movie industry, Bruce actually made his screen debut at the ripe old age of three months in the Cantonese film Golden Gate Girl (1941). Bruce was hailed as a “genius child actor” who appeared in a string of movies including The Kid (1950), Infancy (1951), Thunderstorm (1957) and The Orphan (1960). He was the Jaypee de Guzman of his generation.

He had a tombstone made for traditional martial arts. Bruce asked his friend George Lee to make a satirical replica of a tombstone with the inscription “In Memory of a Once Fluid Man Crammed and Distorted by the Classical Mess.” He felt that traditional marital arts disciplines were “artistic” dead ends that were shackled by their theories, rules and style. This was the reason he developed his own fighting style Jeet Kune Do (the way of the intercepting fist), which was referred to as a “style without style” (sounds like the way I dance) or the “art of fighting without fighting” (I think my wife is secretly a Jeet Kune Do grandmaster). Bruce’s fighting form had “no fixed technical movements, no specific forms.” His last movie The Game Of Death would have featured Jeet Kune Do but Bruce unexpectedly passed away before shooting the film’s fight scenes.

He had killer feet. If you think Bruce Lee’s fighting skillz are scary, then let me leave you petrified: he was a competitive cha-cha dancer who won the 1958 Hong Kong Cha-Cha Championships when he was 18. If he couldn’t beat them street thugs in a street fight, he would definitely take them down in a dance showdown.

After following in the footsteps of Bruce Lee, I now need a heating pad, a deep tissue massage and some tiger balm.